How do children retell «The Mitten» in English and reenact the events of the fairy tale with a real mitten? How do they put the new words into a song and sing it? And how do children learn Japanese and Ukrainian cultures in English? It’s easy with our Japanese teachers!

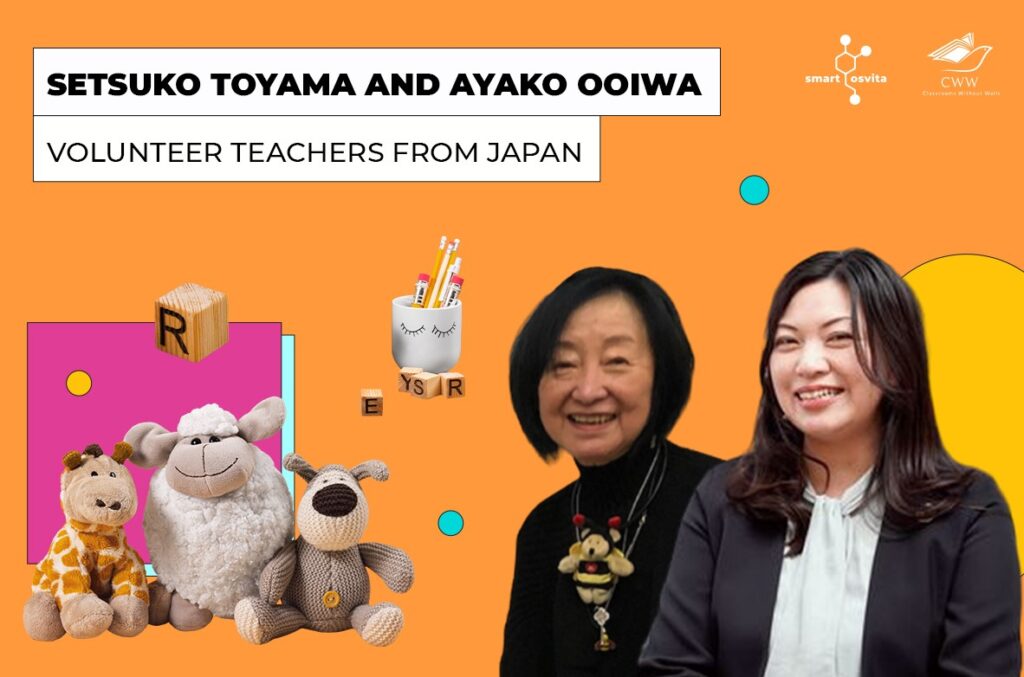

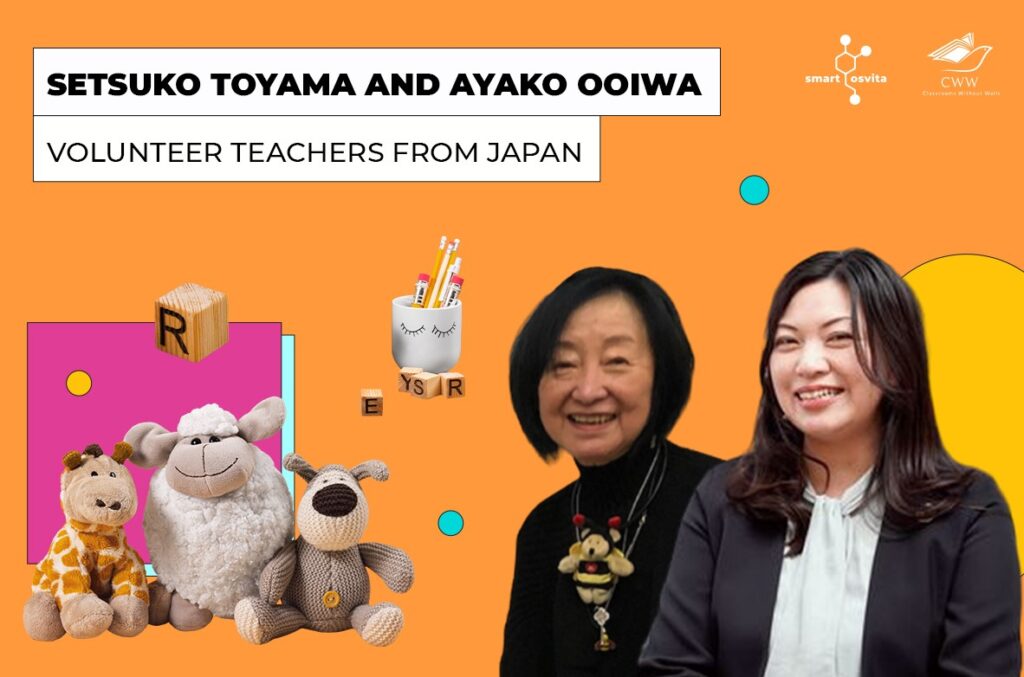

Japanese volunteers Setsuko Toyama and Ayako Ooiwa have taught 120 English lessons to Ukrainian children in our project «Ukraine Speaks English» and plan to continue their efforts to offer lessons as long as there is a need. The volunteers have been teaching English in the project since the beginning of the full-scale invasion. They told us how they integrate Ukrainian and Japanese cultures into their lessons, what Ukrainian children surprised them with, and what motivates Setsuko Toyama and Ayako Ooiwa to continue teaching.

«Every Tuesday after a lesson, I think of this phrase: «Not all heroes wear capes». The Smart Osvita staff, volunteer moderators, and teachers alike, are all heroes who try to make sure that children are provided with fun lessons to focus on, that they are distracted from the reality, and that children’s rights to learn are protected even under this difficult circumstance. I think of my role as a sidekick, to assist the super hero Setsuko-sensei who not only generously provides her amazing resources and experiences to plan every week’s lessons but also comes up with new ideas and techniques to teach in a rather unique and sometimes challenging environment», — says Ayako Ooiwa.

Please tell us what inspired you to join the project «Ukraine Speaks English.»

Setsuko Toyama: It was the message sent out by Smart Osvita to international teachers in March 2022. It said, «Children don’t learn under stress. We need to distract children from reality. We need fun lessons.» That moved me very deeply. Children need to play and learn in a fun and safe environment to grow. No one can take away a happy childhood and opportunities to learn. I was thankful there was a way for an individual in Japan to help and support Ukrainian children. I sent in my application and I conducted my first lesson on March 22nd.

I was fortunate that three friends soon joined in my attempt to teach Ukrainian children online. Ayako teaches with me, Hiroko helps me with preparing resource materials and Junpei helps with technical skills. They also have made presentations on Japanese schools and cultures and contributed to lessons.

What were the important milestones for you during these two years? What was your path in the project?

Setsuko Toyama: I can name two lessons as milestones. One is the career education lesson Ayako and I taught in a middle school. The lesson was interrupted by an air alert. The teacher came up to the camera and said, «Sorry, we have to run.» We saw students stand up pack up their bags and leave the classroom. One student came up to the camera, smiled, and put both hands together and vowed good-bye. They were acting so calmly and matter-of-factly that it struck me deeply how bravely they were living through the challenging time.

Another memorable lesson is one of the public meetings for young children. I read «The Mitten», my favorite Ukrainian folk tale. I used a bi-lingual edition of English and Ukrainian. I had children read the Ukrainian text and I read the English. Then I showed a large mitten I had knitted, put small toy animals into it one by one, and encouraged children to retell the story. It was an English lesson drawing on the Ukrainian culture and we all enjoyed the session.

Please share your approach to leading lessons. What is important to you during lesson preparation? Do you have some plan or tradition?

Setsuko Toyama: Ayako and I try to learn children’s names so we can call them by their names. Our efficient moderators help us by renaming Ukrainian-spelled names to English alphabet. When a child raises their hand, we encourage them to speak up. Sometimes children want to show us their drawing or craft. We also try to show them real things such as a mandarin orange, a persimmon, a rice ball that are ordinary in Japan but no so in Ukraine.

Basically I make lesson plans and Ayako and I conduct activities alternately. I try to make the most of there being two teachers. Ayako and I can model dialogs and Question and Answer and show how to participate in a new activity by one of us being a mock student. I also believe that listening to two teachers speak English to each other is beneficiary to nurture children’s listening comprehension.

I try to keep the routine of starting the lesson with Good Morning Song and ending the lesson with Good-Bye song. I sum up the lesson at the end so children can feel assured and confident that they not only had had fun activities but also had actually learned English.

What are the peculiarities of your lessons? What emphasis do you make in your lessons? (Maybe an individual approach, focusing on the children`s interests, etc?)

Setsuko Toyama: From my experiences of a teacher, a teacher trainer and a material writer, I have found that picture books and music are strong tools for children to learn and acquire English. Children grasp the situation from the illustration, use their imagination to predict what happens next and read the text of which they already know the meaning.

I select a picture book that has a child-friendly topic and appropriate amount of text for the children and make a three-step plan:

- a pre-reading activity in which children pre-learn important words in the story;

- a reading together session in which children can unmute themselves and try to read aloud;

- a follow-up activity in which children review the story and the vocabulary.

I often put target sentences and vocabulary on a familiar melody and have children sing and move their body to show the meaning of the lyrics. One example is singing, «I want a dog. I want a dog. I want a big dog. I want a dog,» on the melody of «Farmer in the Dell.» We changed «big» to other adjectives such as small, strong, funny and sang. It’s more fun to sing the target language than practice substitution orally. The children learn and retain the language more effectively as well.

Every lesson ends with a phonics activity in a quiz format. Children have to guess 10 words that start with the same letter and sound or 10 words that children learned in the story book. Ayako shows the first letter and sounds it out and then slowly reveal the picture while she explains what it is in children-friendly English. She teaches this activity so well that children love it and look forward to it.

What is your experience of working with Ukrainian children? Whether are they interested in learning? What exciting stories did you remember (maybe children have astonished you by something?) What is inspiring you to volunteer in the project and teach Ukrainian students?

Setsuko Toyama: They are very eager to learn and have little hesitation in speaking English. I think they are more of ESL learners than EFL learners. They have good listening comprehension and ask question when they don’t understand. Those are qualities of a successful language learner.

They have a combination of childlike innocence and mature social skills. Some children take time in answering and other children wait patiently for their turn to unmute and speak to the teacher. In short, they are lovable young human beings and I simply enjoy interacting with them. Here’s one example. One child asked me out of the blue, «How old are you?» I answered, «I’m one hundred years old.» The child’s eyes widened and he said, «Are you a witch?» We all had a good laugh.

Sometimes the children surprise me with their unexpectedly rich vocabulary. After we read a Japanese folk tale (in English) about an old man choosing a present, either a small basket or a large. The children predicted the old man would choose a small one. One child said, «If he chooses a large one, he’s greedy. He will get something very bad, like dirt, in a large basket.» I praised him for knowing the word «greedy» and he answered he had learned it while playing a game.

Some children are interested in Japan and Japanese language. Ayako and I model Japanese greetings «Genki desuka?»» Genki desu,» equivalent for «How are you?» «I’m good.» Sometimes children ask me «Genki desuka?» in Japanese before we start the lesson. That makes me very happy. They keep me upbeat rather than I them.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

Setsuko Toyama: Everywhere and all the time. When I see something that clicks in my mind as a material for upcoming lessons, I start thinking how I can use it. The idea is fermented and becomes a tangible activity or plan. One example is «The Mitten.» I wanted the students to learn English and familiarize with their own culture in one lesson. I kept looking for suitable version of the folk tale, found a bi-lingual picture book and was able to use it in the lesson.

Ayako Ooiwa: I get to meet lovely Ukrainian children. I learn their unique language, cultures, and perspectives and at the same time I learn that Ukrainian and Japanese children share a lot in common. With some children, I meet them only once so I try to cherish the opportunity, and with some children I really get to know them as they join the lesson multiple times over a quite a long period of time. There is one girl who has been attending our lesson over the past two years, and she has never missed a lesson. We see her becoming a fluent English speaker, and we see her growing up. When I first joined to support this project, I never expected to have a student like her, who I meet every week, feel so dearly about, and hope for the safety of.

What drives you to move forward and continue volunteering in the project? What are your plans (for the project and in general)?

Setsuko Toyama: It’s the children who take the lessons. Meeting them every week is an important part of my life. Ukraine Speaks English team provides support and directions. The moderators support us perfectly and we owe them so much for making the lesson safe and successful. We the team Japan would like to continue our efforts to offer lessons as long as there is need. Peace will prevail and children will grow up. In many years from now, will they remember international teachers who taught them? I hope they will remember learning English from Japanese teachers.

Ayako Ooiwa: Sometimes people ask me what drives me to continue volunteering in the project «Ukraine Speaks English». It is for myself. To be specific, it is for my future self. I strongly stand for justice. I stand for peace. I stand for children and children’s rights to be children, to receive education, and to live a happy childhood. I stand for Ukraine. I felt so powerless when the invasion started in February of 2022. After years from now when I look back at history, I do not want to say that I lived this time but did not do anything about this matter. I want to be proud and tell my son and my students that I did something, and that I was a sidekick of superheroes.

We are proud and grateful to every volunteer for supporting Ukrainian children and believing in us. The project «Ukraine Speaks English» is implemented by the NGO «Smart Osvita» in partnership with «Classrooms Without Walls»/Teachers for Ukraine.